Abstract Impressionism? The unprecedented encounter between Joan Mitchell and Claude Monet

The retrospective dedicated to Joan Mitchell at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, just like the segment that places her work into dialogue with Claude Monet's last paintings, offers a moment of dazzlement. The surprise of (re)discovering an artist, Joan Mitchell, too long underestimated in favor of her male colleagues – and sometimes friends – is increased tenfold by the exceptional quality of the loans and the intelligence of the exhibition itinerary that links the two projects.

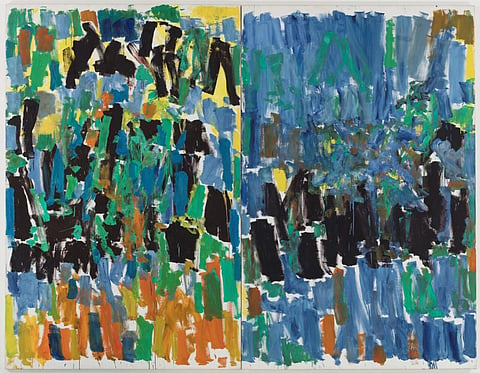

Between the violence, the gestural intensity, and the brilliance of Mitchell's colors, and the contemplative aspect of the Nymphéas [Water Lilies], there is, however, something that clashes on occasion, like two universes whose correspondences we can sense but which struggle to (re)connect with one another. Mitchell herself hardly showed any clear recognition of her filiation with Monet, favoring rather Van Gogh and Cézanne. The encounter is essentially based on Vétheuil – the village where both artists lived and worked over long periods – and on the matter of landscape, which serves as a guiding thread through the exhibitions. By linking Mitchell to Monet, not only do the curators raise the question of the relationship between abstraction and Impressionism, but above all they invite us to question the place we give to abstraction today and the readings we make of it.

Reading Mitchell's work in the light of Impressionism highlights what she described as 'feeling' – the sentiment that seems to move her to the act of painting. Yet, 'feeling' cannot be entirely associated with impression. The confusion felt by the visitor who has just walked through the monographic galleries when first faced with the conjunction of Monet's and Mitchell's paintings betrays this: The solidity, the chromatic power of Mitchell's paintings seems to submerge the 'floating,' almost evanescent character of the water lilies, and it takes a few moments for the eye to become accustomed to passing from one to the other. The 'impression,' being of the psycho-physiological order, is mainly a matter of perception; here, that of a weakened, nearly blind Monet, who, by way of the monumental, by way of certain spectacular impastos, attempts to take form in his painting once more. On the contrary, 'feeling' is of the affective order; in the American artist's work, it materializes through the visibility of the gesture, through drips that recall the speed of its action, the explosion of colors that owes so much to Van Gogh, and beyond him to the Romanticism of Delacroix. The fact that 'feeling' took shape in this bodily painting signals that it can no longer be considered to belong solely to the order of the 'state of mind,' for which landscape is construed as the projection surface.

And thus, we come to question the importance of biographical interpretation, so often adopted to illuminate – if not explain – Mitchell's body of work (separations, mourning, travel, and so on). There is a paradox in seeing biographical overdetermination applied in the interpretation of a body of work that is above all abstract. One wonders if it would have been so frequently employed had the artist been a man – especially since most of the time we are referred to sad passions, between mourning and melancholy. Of course, Mitchell played with this by way of the titles she gave to many of her paintings, such as La Grande Vallée (1983) and No Room at the End (1977). On one hand, some of these titles were chosen after she had begun to paint them – sometimes during the 'title evenings' mentioned by her friend, the artist, composer, and educator Gisèle Barreau. On the other hand, to what extent can we take this playfulness of hers as a fundamental element of interpretation? Taken too literally, the interpretive filter imposed by the title, as meaningful as it is, stifles the irony or self-deprecating irony that animates many of her compositions. When, after her separation from the painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, she began to paint La Vie en Rose (1979), she did so with great black brushstrokes. An allusion to Edith Piaf perhaps, but also a way to empty affect onto the canvas.

Conversely, by re-reading the Impressionism of Monet's last works through the prism of Joan Mitchell's painting, we better understand the fugue that plays out through the exhibition. The great lesson of this rapprochement is not so much to underscore influences by introducing continuity, but rather to show Mitchell and Monet in a different light, by illuminating one through the other and shaking up classifications. Because what is essential in the dialogue is the appreciation of the fundamental rupture introduced by abstraction. 'My painting is abstract, but it is also a landscape,' Mitchell liked to say, as though she were trying, in spite of everything, to pick up the pieces of a history of painting and to glue them back together. The final crescendo of the exhibition, where the two artists are brought together in full, with Mitchell's Edrita Fried (1981) and Monet's Les Agapanthes (1914-26), unfolds in the register of the monumental, of the disproportionate even, as the viewer is delivered back to their sensoriality, and their subjectivity is immersed entirely in the painting.

Sébastien Allard is director of the department of paintings at the Musée du Louvre.

The Estate of Joan Mitchell is represented by David Zwirner (New York, London, Paris, Hong Kong).

'Claude Monet – Joan Mitchell, Dialogue'

'Joan Mitchell, Retrospective'

Through February 27, 2023

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris

Caption for full-bleed images :

1. Claude Monet, Nymphéas, 1916 – 1919. Courtesy of Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

2. Joan Mitchell, Plowed Field, 1971. Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris © The Estate of Joan Mitchell

3. Joan Mitchell, Minnesota, 1980. Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris © The Estate of Joan Mitchell

English translation: Jacob Bromberg

Inspired by what you read?

Get more stories like this—plus exclusive guides and resident recommendations—delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to our exclusive newsletter

Resident may include affiliate links or sponsored content in our features. These partnerships support our publication and allow us to continue sharing stories and recommendations with our readers.